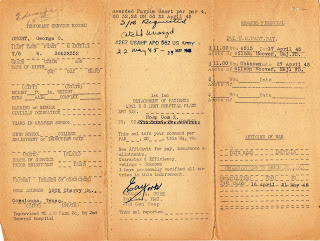

This is the third and final part of the memoir of George Olsson Short, whose family love of baseball was a feature of his boyhood in the Texas of the 1920s and 1930s. After earning a living he went to Europe to fight for his country. Surviving a day in Germany that almost blasted him to pieces he learned another meaning for the term “home run”. In this final part, George relates how his soldier brother became his savior and how he managed to get home to a post-war Texas life.

It was night and I had been lying in that snowy freezing plowed field all day when I heard voices. Two graves registration people were picking up bodies. One of them discovered I wasn’t dead so they put me on a litter and carried me back a few hundred yards to a “six by six” truck that had been converted to a mobile operating room. One of them knocked and the door opened to a very dark room. They laid my litter on a table and as soon as they left and closed the door, the lights came on. Two doctors asked me where I hurt the worst. I told them the two good sized pieces of shrapnel sticking out of the back of my head were really hurting. They said they were not equipped for that. So they took shrapnel pieces out of my leg and left shoulder. My thumb was mostly gone. They told me they had no more morphine or anything else to stop the pain so sulpha powder was sprinkled on everything and the shrapnel was left in my head. My litter was moved to an ambulance along with six other wounded men on litters and a convoy of ambulances started back through the woods and the German soldiers. Along the way, the Germans used the red crosses on the sides of our ambulances for target practice and some of the wounded were shot again. Two of the six in our vehicle were D.O.A. when we finally got to the tent hospital.

Our litters were lined up on the ground in the snow in the order of worst first. My memory is very hazy but I remember a medic slitting my pants legs, sticking my luger under my back so no one would see it and telling me I was next. My litter was placed on two wooden saw horses and a major and a nurse were looking me over. The nurse told the Major she was giving me the last of the pentothal anesthetic. When I came to, they were trying to put a thumb from one of the D.O.A.s on what was left of my right thumb. I was cussing the major in between bouts of consciousness. They finally got most of the metal out of my head and, still on my litter, I was put in another ambulance and taken on a rough ride to the air strip at Kassel. We were put in a DC3 plane, converted to carry litters. Web belts were hung from the ceiling with pockets to hold the four ends of the litters, almost like hammocks. Our arms and knees were strapped to our litters to keep us in.

They had brought two DC3s in to get the most seriously wounded out. This was my first time in an airplane. There was still no morphine so I was in and out of consciousness. The pilot came to the door and told us he was Captain Cunningham and we could relax and enjoy our trip to Rheims, France. We were on our takeoff roll when suddenly the left wing and prop hit the ground. The plane cartwheeled and turned upside down, leaving us hanging by the straps on our litters. They got us out in a hurry and put us in the other plane, over a lot of our objections. The Captain came in and told us he had hit a soft spot on the runway from a shell hole that had not been repaired properly and this time we were going to make it to Rheims. (I remembered Captain Cunningham’s name and several years later I saw him again on a domestic flight to Chicago and we had quite a nice reunion.)

When we got to Rheims we landed on a conveyor belt runway that scared the hell out of us. As soon as the plane doors opened, nurses came in and gave us all big shots of morphine. I passed out until I remember taking off again on this same noisy runway and the nurse telling us we were going to Nancy, France to the 2nd General Hospital run by the U.S. Military, as the Rheims facility was full.

When I waked up again, I was in a bed in a ward in the Nancy hospital. I remember hearing an argument about what to do with the little white worms crawling around my hand. They finally had a ward boy use tweezers to pick them out. Sometime later, they took me to the operating room and took the bones out of my thumb as it had swelled and was infected. They were going to amputate at the elbow, but I objected as strenuously as I could. The next day I was overruled by a board of three doctors who unanimously agreed on the amputation. I was scheduled for surgery the next morning at 7 a.m. and was severely depressed. I was back on the ward when I looked up and saw a tall filthy dirty soldier standing in the door of our ward. “I’m Lieutenant Billy Short and I’m here to see my brother George.”

My brother Bill had received a note from a Red Cross lady who wrote letters for soldiers whose injuries kept them from being able to write. She had written to both my wife Mary Cate and Bill. The letter told him I was wounded and in the Nancy hospital. Bill was at the time in the 87th Infantry Division, a part of the Third Army and was up close to the Czech border. He was part of the Quartermaster Corps, in charge of a supply company that brought gas and ammo up to the front lines, the most dangerous job in the Army. He had traveled for two days and nights. He said he had asked for permission to leave and being denied, had left without permission, hitching a ride with a general who was going to Nancy. Somewhere along the route, the Germans had put some roadblocks in the road and they hit them, wrecking their car. Bill and the General both received some cuts, but none were life threatening.

I told Bill I was scheduled to have my arm amputated the next morning and asked him to help me get out of there. He said, “Let me see what I can do.” He convinced the nurse he was taking me for some fresh air and picked me up in his arms and carried me down four flights of stairs to a Jeep he had “borrowed” from a chaplain. We checked in to the B.O.Q. (Bachelor Officers’ Quarters) in downtown Nancy. I weighed less than 120 pounds and had bandages all over my head, my right foot, leg and my stomach. My right arm was yellow, swollen and stinky and still had some maggots.

The next morning, Bill shook me awake and said “I’m taking you back because you’re going to die if something isn’t done.” He took me back to the hospital and found a big ward boy to help him carry me up. As we reached the ward, a doctor standing there asked me if I was George Short. He asked me if I would let him take a look at my arm as he was a specialist in hand injuries and had flown in from London that morning after the fog had lifted. They took me to a treatment room and after an exam he told me there was a slight chance of saving the arm but that if it didn’t work they would have to amputate at the shoulder instead of the elbow. Both Bill and I agreed and they started treatment immediately. The treatment began with scrubbing my arm with a brush in a big pan of warm water with green soap. The doctor then wrapped it and an orderly poured warm saline solution on it for six hours. Bandages were changed and new bandages were applied and my arm soaked in warm mineral oil for six more hours. Bill told me most of this because I was in and out of it most of the time. The bandages and solutions were then alternated every three hours and by the next morning all the terrible stench was gone and my arm was almost back to normal instead of looking like a green, black and yellow football. I knew then that they had saved my arm. Both Bill and I wept with relief. The doctor then operated and tried to use a bone from the bone bank to make me a thumb. It was rejected and after about a week they took it out. In the meantime, they took the shrapnel out of my head, foot, leg and the bullet out of my shoulder.

After the surgery, Bill stayed with me a few more days and then had to get back to his outfit. Before he left, he said he wasn’t sure we’d both survive so we should have a photograph made. He took me to have our picture taken in downtown Nancy, thanks again to the chaplain’s Jeep. (When he got back to his outfit, Bill was denied his battlefield promotion and almost had his rank lowered for leaving without permission.)

The photo taken in Nancy, France.

Bill is on the left, George in front with a jacket draped over his wounds.

Our younger brother Bob missed the European conflict but was in the first group of soldiers who entered Hiroshima, Japan after the surrender. He said it was the most horrible thing he ever saw.

On May 8, which was my 25th birthday, I woke up to the ward boys pulling down the blackout drapes and telling us the war was over. I had gotten my vision back by then and my head was almost healed. My thumb and stomach and foot still had bandages. Sometime later, they put us in ambulances and took us to a tent hospital just above Omaha Beach at Cherbourg to wait for a ship to bring us back to the States. This hospital was located next to the cemetery by the beach.

We were finally put on the S.S. Mariposa, which had been converted from a luxury liner to a hospital ship, and sailed on 17 October 1945 for Boston. I was still on a litter and couldn’t walk so they carried me to the dining room with the other wounded and propped us up so we could eat. The middles of the tables were full of pitchers of fresh milk and both chocolate and vanilla ice cream. I downed two glasses of milk and some ice cream. We all threw it up in a bucket that was ready for us. I remember dong this three times before they stopped me and fed me some regular food. Eating real meals again, I must have gained ten pounds during the six days before we got back to Camp Miles Standish in Boston on October 24.

We were there for a few days and then put on a hospital train going to Okmulgee, Oklahoma, still on our litters. Several days later, about the middle of June, we arrived at a new hospital built to take care of German prisoners of war. They wouldn’t let us go in the hospital because it still had German P.O.W.s in it so they made us stay on the train for three more days. The air conditioning only worked when the train was moving so we were in a stinking hot mess. I took this rather hard because I remembered how our own boys were treated at Limburg, Germany with a new hospital sitting empty. We finally got into the beautiful cool hospital and were given baths. I don’t know or care where they moved the P.O.W.s., but it had to be far better than where our boys were put in Germany.

We had been told in Boston that those of us that weren’t critical would be allowed to go home for thirty days. After waiting a few days for classification, I was classified critical and scheduled for an operation five weeks later. (They must have had a loose definition of “critical.”) The colonel who was running the hospital treated us like the German prisoners he had been used to handling. (We were told he was unreasonably tough.) I got one of the ward boys to wheel me to the colonel’s office to get an appointment and was told I couldn’t have an appointment for a month and he wouldn’t see anyone without an appointment. (Maybe this guy was a German?) I barged in and I told him I wanted my promised thirty days leave and would be back in time for the operation on my hand and I needed some clothes as all I had was the gown I got in Nancy, France.

He was very angry and ordered M.P.s to take me back to the ward and confine me to it. He said he wasn’t giving any of us thirty days leave. He also said he was going to bust me back to a private for barging in on him. I told him I was already a private so go ahead. (That’s when I found out I had been given a battlefield promotion to some kind of sergeant.)

That night with the help of some ward boys and others, twenty-two of us revolted and stole some uniforms and went to the train station at eleven o’clock to catch the train to Dallas. None of us had any money but we were ready with I.O.U.s to give them. The people running the station said they would not take the I.O.U.s and tore them up and helped us onto the train. The people in the Pullman section gave us their beds. The porter picked me up and put me in a bed where I fell asleep until we arrived in Dallas at 6 a.m. the next morning.

When I worked for Rath Packing Company we were two blocks away from the station and post office and I knew the area well. The conductor told us that if we walked through the station, the M.P.s would pick us up so I took everybody through the back of the station and through the post office. The cab station was right there. I got home and about three weeks later I got a phone call from the M.P. office. After telling them my story they told me if I would be back before thirty days they would leave me alone. Before the deadline, my wife drove me back to Okmulgee and I went right back to my bed in the ward.

A little later, I was taken to the Colonel’s office and he said I was confined to my bed, busted in rank and would be court-martialed. I later found out he could not do this as I was a wounded-in-action soldier needing operations. Two days later, the Colonel was replaced. The rumor had gotten around that he was not long for this world as the whole hospital was rebelling against him, including the doctors and nurses.

I had another operation on my thumb and they took a piece of bone out of my leg and put it in the thumb. I was told I would be at least two weeks in bed which was standard Army protocol. Three days later I went back home to Dallas, again without permission. Three weeks after that the M.P.s called so I went back to Oklahoma. This time they scheduled me for surgery the next day and they sewed up my stomach. This was a blessing as I got rid of a big bandage around my waist that was very uncomfortable. The new colonel told me I could go home legally for a month if I would stay in bed there for two weeks. At home, my thumb swelled up again and I went back. This time they took some bone from a bone bank, drilled a hole and put a pin in all the way to my wrist and a cast to stay on six weeks. Three weeks later, it did not work so they put six of us in an ambulance and drove us to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. There, I was patched up and told there would be more surgeries later.

I wanted out and I offered to sign away all my rights for disability if they would let me go. I had to get a dental clearance and a Disabled American Veterans clearance first. I met a Captain in the dental corps and he said if I could stand it to come in the next morning at six a.m. and he would try to get it all done. I was pretty bad, as I had gone almost six months on the front lines with no tooth brush. At 8 p.m. the next day he signed off with me minus a few teeth and a bunch of new fillings. The next morning I was at the D.A.V. office and told them my tale of woe. This was the 23 day of December 1945 and I wanted out that day. I was assigned to a wonderful vet who told me if I would give him the rest of the day to do my paper work he would have me discharged first thing in the morning. I agreed and signed everything he put I front of me. (Gratefully, he didn’t do what I asked and, unknown to me, kept my disability rating for me.) At 8 a.m. I was discharged. Two hours later I was on an airplane to Dallas.

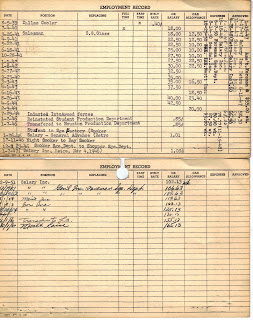

A week later, I reported back to Rath, ready to go to work. They decided the shape I was in made me a candidate for their first sausage school and they transferred me to Houston, Texas. I bought a new 900 square foot home for $4,400.00, put $400 down and moved in. About two months later I received in the mail a check from the V.A. for several hundred dollars which was two months disability pay for being classified 100% disabled. At that time, I was making twenty-four dollars a week and could certainly have used the money, but I was sure there was a mistake so I took the checks to the V.A. and they told me I would have to be seen every three months for a years, primarily because of my head injury and to go ahead and cash the checks as I would be re-evaluated. After about a year, they cut me to fifty percent and for ten years I had to go through evaluation every year. I was certainly glad when that was over as I also had to see a psychiatrist every time.

About two months later, my thumb was giving me a lot of trouble and I went to the Veterans’ Hospital in Houston and after about six hours of getting no satisfactory answers, I blew my stack and started to leave. A doctor stopped me and said, “Let me see your problem thumb.” He took me to a room and after examining me said, “I helped operate on you in Nancy, France and the doctor who saved your arm is in New York.” He picked up the phone and called him and the New York doctor said he had a schoolmate practicing plastic surgery in Houston and he would get in touch and be back to us. I was thanking Heaven. The New York surgeon offered to do the work free if I wanted to come to New York or his friend would do the work there. Two days later I was an outpatient and had the operation over with. He took bone from a bone bank and used a pin and a cast. Two months later I went to his office to get the pin removed, which I feared dreadfully. He took the cast off and I told him I couldn’t wait any longer and to get it over with and pull the pin out. He told me he had already done it several minutes before.

I finally had a thumb instead of a nub. After he took photographs, I went down to my car, reached for the door handle, hit my thumb and busted it again in two places. It stayed that way for fifty-three years until I found a hand doctor in Long Beach who told me he could fix it while he was doing some more surgery. At last I had a usable thumb, ½ inch shorter than my other thumb, but I had a thumb.

Note: George ended his wartime narration here. He learned well the early lessons of his work in the meat packing industry and began an successful business in California making hot dogs for wholesale markets, such as Der Wienerschnitzel. His company Western Treat became the largest manufacturer of hot dogs on the West Coast.

George and Mary Catherine “Mary Kate” Novotney Short had two children: Fred Olsson Short, born 24 January 1942 and Susan Catherine Short, born 26 January 1944.

Freddy married Sharon Lee “Sherry” Sandstrom in 1964. They had a daughter, Lisa, in 1968. Freddy was killed when he was hit by a car while changing a tire on a Los Angeles freeway in 1970. Susan married David L Fallen and they had two sons, John and James.

Mary Kate died in 1980. George later married Joan Pampinella and they lived happily until his death. He died in Newport Beach, California 14 July 2003. His brother Bill died in Laguna Beach, California in 1996. His brother Bob died in October, 2012 and sister Betty in 2001.

* As a footnote, the first time Bill’s family heard this story was over a dinner George shared with Bill’s son, Bill, Jr. George opened the conversation with, “You know your father saved my life during the war.” As he told the story, they both wept.

(This narrative was compiled by Dianne West Short, daughter-in-law of brother Bill. The facts were pared with the assistance of writer Patrick Cornish in Perth, Australia.)

© Dianne West Short – 2012-2016 All rights reserved.

One thought on “Surviving and Arriving Home”