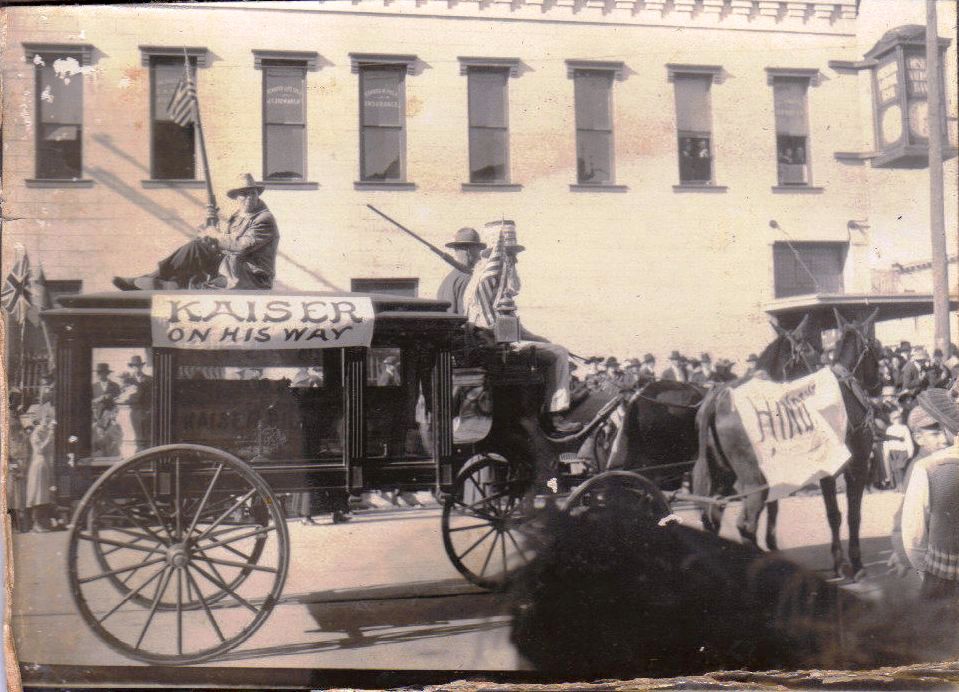

A downtown parade was among the most exciting events of a childhood spent in a small Texas town. In our old family albums are photos taken by my grandfather of the 1918 Armistice Day Celebration with streets jammed with men and women and an Uncle Sam-driven, mule-drawn hearse with signs symbolizing the end of Kaiser Wilhelm. And a 1920 “May Day” when a parade filled downtown Corsicana streets with flower-decorated cars and a special rose-festooned carriage for the May Queen.*

In my own memory, parades celebrated such things as the opening of the Rodeo or important football contests like Homecoming. Uniformed marching bands with gleaming instruments, local ranchers and farmers on silvered horses, pretty girls in strapless gowns waving shyly from the backs of convertibles. Home-made floats advertised neighborhood businesses and local men’s organizations marched with fezzes and ribbons. And small children darted out from curbs to capture tossed candy. Everyone smiled. Everyone.

The pomp. The pageantry. Such glorious memories.

All parades were exciting but for me nothing beat a circus going down a hometown street. Colorful painted cages of wild animals, acrobats in fairy-like sequined costumes, trapeze artists swinging on a flatbed truck, clowns passing out candy and beautiful prancing horses. What could possibly top that?

Well, something could. The thing I most wanted to see was an elephant. Photographs and movies cannot compete with the sheer majesty of such a creature before your eyes.

Elephants, however, were responsible for several Corsicana tragedies.

1929 was the year a nine ton male Indian elephant named Black Diamond came to Corsicana.

Advertised as being the largest and tallest Indian elephant in captivity, the 31 year old pachyderm was part of the Al G. Barnes Circus. Black Diamond was later described as “moody” and unpredictable. He was also an elephant who had been labeled a “runaway.” So, the circus usually kept him chained between two calm female elephants. Additionally, his tusks had been cut and a bar bolted across them to limit his trunk movement.**

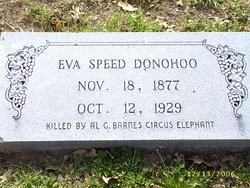

Diamond had been owned by a man named H. D. “Curley” Pritchett who had gotten him from his brother-in-law. After 7 years together Curley and Diamond had formed a bond, whether based on kindness or cruelty is not known, but a bond nevertheless. In a 1929 newspaper interview, Pritchett said, “He was awfully jealous of me.” However, in 1927, Curley sold his elephant to the Barnes Circus for $3,000 (a low price due to the elephant’s intractability), essentially abandoning him. Then Curley moved to Kerens, in the Corsicana area, to work as a ranch hand on the “Shoestring Plantation” for a woman named Eva Speed Donohoo. Mrs. Donohoo had been the society editor of the Houston Post and a public stenographer. After inheriting part of the plantation, she had moved to Kerens with her daughter Louise, where she continued writing newspaper articles. The sale of Diamond and Curley’s move to Kerens was said to hadve been negotiated with Mrs. Donohoo while Diamond grazed quietly on hay next to them, a fact that likely played prominently in future events.

Diamond having been the largest thing in his life prior to Kerens, Curley often talked about him to his new employer, Mrs. Donohoo. When he learned that the Barnes Circus would be coming to town, he invited Mrs. Donohoo to see his old friend, and to perhaps demonstrate his mastery of such a magnificent creature. So on October 12, 1929 see him she did…and Black Diamond saw her.

At the train yard, the equipment and animals were being quickly unloaded. The train had been delayed by a wreck and the circus employees were rushing about to ready for the parade through downtown. After Diamond came out of his steel-bottom train car, Curley moved forward to take his familiar “control” of the elephant. Then Diamond spied Curley and also saw Mrs. Donohoo, who he apparently remembered.

Indeed, elephants are famous for their long memories.

Eighteen thousand pounds charged forward, fixed an angry eye on Curley, then grabbed him with his trunk and tossed him over an automobile, breaking his arm. Then he was on to what appeared to be his main target and enemy, Mrs. Donohoo. After pushing her to the ground, he shoved a vehicle onto the 52-year-old woman. Three times spectators tried to rescue her and each time Diamond dragged her back, finally finishing the job with another large object.

Diamond was finally subdued after three female elephants were chained to him. He was taken back to his boxcar where he was chained, rocking the car and trumpeting for hours. When he finally quieted, he refused food or water. Mrs. Donohoo was laid out on the grass until an ambulance came and took her to Corsicana Hospital on Sixth Avenue.

Curley survived, Eva Donohoo did not. As tragic as the fates of Curley and Mrs. Donohoo were, there was further tragedy to come. What to do about Black Diamond.

Hometown citizens demanded Diamond’s death, but circus officials refused, saying he was in too dangerous a condition to handle. Diamond had apparently been blamed for at least two previous deaths of circus employees described as “show people, one a negro and an old man 82 years old,” as though the two didn’t matter because one was a “negro” and the other “old.” This most recent episode, however, was far too public to ignore. The Barnes Circus people telegraphed for guidance to famed circus owner John Ringling, who was at the time in negotiations to buy the Barnes Circus. Four days later, he instructed that the elephant had to be put down.

But how? Corpus Christi offered to drown him in the Gulf of Mexico. Circus officials thought of putting a circle of chains around his neck and having six elephants, three on each side, tighten chains to choke him. They tried using 1,200 grains of cyanide in a crate of oranges (his favorite food) and in peanuts. He wouldn’t be lured by them. So it was decided he would have to be shot. And of course there was also the questions of what to do afterwards with eighteen thousands pounds of elephant.

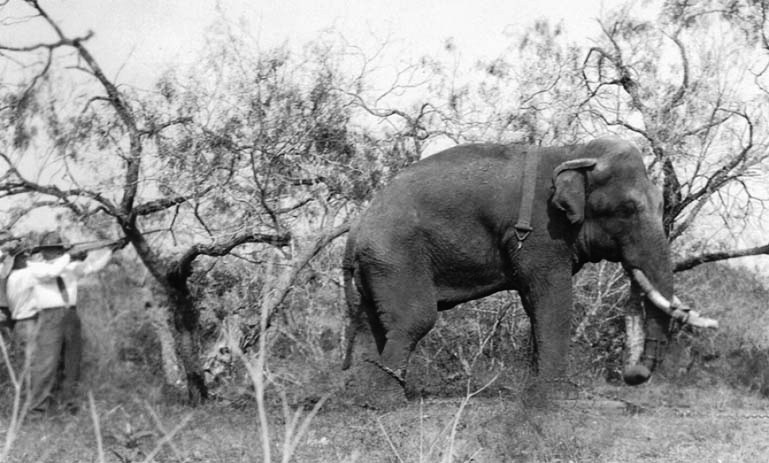

It was finally decided he would be shot in a place that offered easy removal. He was taken to Kenedy, Texas and on 16 October 1929 he was moved into parade formation, led by three female elephants and taken a mile west of town. There he was chained to three huge mesquite trees. His feet were chained together as sobbing circus people and a few townspeople stood nearby while five men sprayed over 150 bullets into him. His great heart finally succumbed to a kill shot at 2:15 p.m. Then Diamond’s remains were divided: his head to a Houston Natural History Museum, his feet that had served man for so many years were to be made into stools. An ignominious end for a glorious creature who hadn’t asked for any of it.

The Black Diamond story was told to me by my parents and grandparents over the years. I always cried…for the elephant.

It took a further incident years later to prompt a call to ban elephants openly parading through Corsicana’s public streets. This time the episode, gratefully, had no actual fatalities, only near-fatal blows to social standing and pride.

The Clyde Beatty Circus came somewhat regularly to Corsicana in the 1950s of my childhood. Born in 1903, Clyde Beatty was nothing if not a showman. Joining the circus as a lad to clean cages, he rose to be a circus impresario. He anointed himself THE “world famous lion tamer,” as though there were only one.

A tireless self promoter, he would flamboyantly stride into a cage in center ring in full great-white-hunter regalia, wearing a safari shirt, sleeves rolled up, riding pants and tall shiny boots, a pith helmet, a pistol strapped to his side, a whirling whip in one hand and the ubiquitous lion-tamer chair in the other. There, he would bravely “tame” his dangerous animals. Beatty was quite entertaining, if perhaps foolhardy and overconfident.

Every few years, the Beatty Circus would come to Corsicana, set up tents outside town and hit Corsicana’s two main streets for a parade to draw the crowds.

On this year, half the county turned out to watch the stream of performers. The clowns were somersaulting, honking bulb horns, and driving tiny cars. The horses were gorgeous. The trick dogs amazing. I think there may even have been a camel decked in braid and velvet. Then came a line of elephants, each holding with its trunk the tail of the one in front of it.

Surprisingly, behind them, moving slowly, was a plain family sedan, its windows open in the summer heat, driven by a local man with his wife beside him in the passenger seat.

Hollis Talley wore a fedora and a bewildered expression. Ardell Talley wore an unflattering cloche hat and was ducking lower and lower, her vision locked straight ahead as though traveling on a barren country road instead of having hundreds of pairs of eyes trained on them. The Talleys had inadvertently turned their car into the parade and because the cross streets were filled with spectators, had been trapped and forced to inch along behind the elephants until they could exit. We all recognized them: they sat behind us at church every Sunday. An odd turn of fate to happen to such a pious, straight-laced couple who almost never spoke to others.

The parade halted, its forward progress temporarily delayed by some difficulty up ahead. The elephants relaxed and the last one in the line decided to relax by backing up to sit against the passenger door of the Talley sedan.

Resting, however, was not the only thing on the elephant’s mind. As soon as Mr. Talley realized that the elephant was beginning to leave a rather large deposit inside their car, in Mrs. Talley’s lap no less, he frantically stretched across his screaming wife and began struggling with the roll-up window to close it. Useless effort as it turned out, because the elephant was sitting on the edge of the glass.

Then, the elephant, apparently finished with its job at the Talley sedan, stood back up and calmly reclaimed its place in line, moving forward. The sedan, however, did not move….but the Talleys did, and rather quickly. As both front doors sprung open, onlookers were treated to the sight of two of their very own, shell-shocked and filthy elephant war survivors.

Our family and, I suppose, the rest of our church parish never looked at the Talleys in quite the same way. For my own part, I can’t imagine that their sense of dignity ever recovered. One noticeable change was they moved from their usual seat on the pew behind ours to the semi-anonymity of the back of the church.

(Note: The names of the Talleys are changed. The rest is as factual as my memory allows.)

*The “queen” in the photos was U.S. Representative Luther Johnson’s daughter Mary Frances.Senator Johnson was a hometown boy.

**(All this behavior was likely due to the poorly understood state of “must” in male elephants.)

Two Tragedies

The end of Mrs. Donohoo

© Dianne West Short – 2014-2016 All rights reserved.

One thought on “Elephantine Memories”