This is the second in the series of three parts which are a compilation of the writings of George Olsson Short, whose family love of baseball was a feature of his boyhood in the Texas of the 1920s and 1930s. After earning a living he went to Europe to fight for his country. Surviving a day in Germany that almost blasted him to pieces he learned another meaning for the term “home run”.

Within a few years of my mother’s death in 1925 and my father’s marriage to her sister Goldie, our family had grown by the arrival of my half-brother Bob, born in 1926 and half-sister Betty in 1928.

By 1932, when I began high school, the world was clouded by the Great Depression. Everyone who had the opportunity to earn a dollar did so. I used to ride into town with Dad at 5 a.m. and go home with him about 6 p.m., working at Armour before and after classes, as well as on weekends doing odd jobs around Rosenthal’s Packing Plant. I later went to Sunset High School in Oak Cliff, a suburb of Dallas, and played football and, of course, baseball.

From 1933 to 1936, I drove an Armour truck – those were the days before driver’s licenses – as well as working inside the plant as an apprentice beef boner and cattle knocker on the kill floor.

In 1936, Dad was transferred to San Antonio and I graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School with the Class of 1937. That same year, our family moved back to Dallas. I worked during the following summer and fall for Boren Packing Company in Dallas and then enrolled in Texas A & M College for one semester.

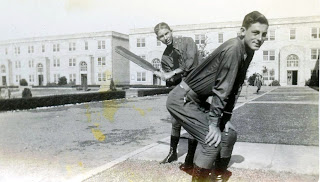

A & M was an all male, all military college. Working to make the $300 needed to attend one more semester, I ran the laundry at the project houses where all the freshman athletes lived. These were built by the owner of Liberty Magazine as an experiment in low-cost housing. We were four men to a room and eight rooms per house, plus kitchen and room for the house mother. Keen to learn how to cook, I worked in the kitchen for dinner seven nights a week. Academically, I did OK, getting an A in all subjects except calculus, which I failed both semesters.

After that semester, it was the end of school for me, as I was promised a job at Rath Packing Company in Dallas, mainly unloading box cars and putting orders in the coolers. After they found out I could drive a truck, I was given a long-distance route. I started at 3 a.m. for the 24-hour round trip, three times a week for about six months before an opening came up on the sales force. Calling on restaurants and bars all over Dallas County, my weekly wage was raised to $18 but bonuses for handling items such as jars of pickled pigs’ feet and Polish sausage more than doubled that.

Meeting Nurse Novotny….and getting a uniform

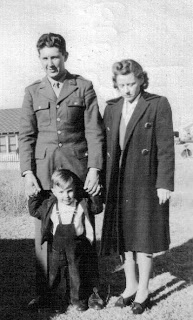

One of my customer accounts was St. Joseph’s Hospital and Nursing School and it was there I met the woman who would become my wife. We married July 4, 1939. Rath moved Registered Nurse Mary Catherine Novotony (Mary Kate) Short and me, still 19, to Corsicana, between Dallas and Houston in early 1940. Our son Fred was born in Dallas on January 24, 1942. This was just after Pearl Harbor and the country was in turmoil.

The next transfer was to Tyler, Texas and there I was called before the Draft Board in 1942. They gave me a one-year deferment and I was actually drafted in August of 1943. By then, the tide of war was turning in the Allies’ favor but there was still a major task ahead in Europe, as I would discover. The day I reported for induction, about twenty of us were put in an open air bus with only benches that had been used to haul passengers around fair grounds. It was a twenty hour drive to Fort Sill, Oklahoma where we became privates in the U. S. Army.

Fort Sill was the Army school for cooks and bakers so I was sure this would be my duty in the Army. We were issued uniforms and given vaccinations and three days later put on a vintage 1920s train with blackout curtains and sent to Little Rock, Arkansas for 16 weeks of training at Camp Robinson. The four-day trip included several breakdowns but one brought a stroke of good luck. We stopped about fifty yards from Will Rogers’ home and we got to see it.

Training began at four in the morning and ended about nine at night. Having weighed 257 pounds on induction, 11 weeks later I had slimmed to 169. My military training at A & M and two years of R.O.T.C. (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) in high school gave me the chance to go to Officer Candidate School, which I stupidly turned down.

After eleven weeks of training, I was given a ten day en-route furlough and told to report to Ft. Meade, Maryland, where I found out about Army inefficiency. We were given the same round of shots as at Camp Robinson, as our records had not caught up with us. More uniforms were issued. Another vintage train with blackout windows took us to Camp Miles Standish, forty miles from Boston. This was the port of embarkation for troops going overseas.

There, our records still hadn’t caught up with us so we were given yet more shots. Greatcoats were issued for our transfer to Europe. In Boston Harbor, 2,400 of us boarded a Liberty Ship, the U.S.S. George Washington Carver, which had an English crew. Bedding down in hammocks in the hold we felt the ship move off about 4 a.m.

About two hours later, a German U-boat sank one of the troop ships in our convoy. The Destroyers that were protecting us dropped barrels of bombs they called “ash cans,” causing underwater explosions that almost split our hull.

The rough seas and oncoming winter (1943-44) brought discomfort all around. Even our medics were sick. Seeking a change from beans, stale bread and hot black coffee, I sneaked out one night and found a case of Milky Ways. Most of our guys, however, were too sick to take up the offer.

At the French port of Le Havre, our entry to Europe, the U.S. Air Force and Royal Air Force had bombed the harbor until there were no docks left. The ship was brought as close as possible to land and the Corps of Engineers dropped a long-masted crane to meet our gangway. We were warned to walk across carefully. If anyone fell off they would freeze before being rescued.

Carrying full duffle bags and rifles, we marched to the rail yards and boarded World War I “Forty and Eights,” boxcars made for either 40 men or 8 mules. Jammed inside, with the doors locked, we used our coats and bags as mattresses. Outside it was about minus 10 degrees and not much warmer inside. We used one corner for a toilet and got fresh cold air through one opening at the top of one side.

The next three days are a blur as we were so cold no one moved much. At night, we were allowed off for coffee and some kind of mush. On the fourth day we stopped at a siding next to a building for training Lipizzaner horses. Each one of us had to be carried to fires lit in the center of a training ring, which thawed us out but because we had frostbite, brought the worst pain I had experienced in my life. They gave us each a shot of morphine, some hot food and two blankets. As a snowstorm raged, we were wished a Merry Christmas… “Welcome to Belgium and the Bulge.”

Arriving later at a reppo-deppo (replacement depot) in the north-eastern French city of Metz, we were loaded into “six by six” trucks and headed to the front lines.

It was a time of desperate measures. Assigned to a tank corps, I learned to drive a Sherman tank in the bare two hours we had before we moved out in a convoy. With booms from the front only a couple of miles away, it was daunting seeing ambulances lining both sides of the road. I was shaking with fright as we moved towards the Siegfried Line, a supposedly invincible set of German fortifications.

Our 9th Army advanced much faster than expected and the Germans retreated in panic. Our kitchen truck couldn’t keep up so we had to search for food in deserted German homes. I found a 3 foot diameter iron skillet that must have weighed at least fifty pounds. I hit every hen house and grabbed all the eggs and a couple of young hens. Egg sandwiches on black bread were a treat. I had also found a big tin of ersatz butter so everything, including the hens, was cooked in the skillet. The next time I lost a tank, however, I lost my skillet as well as my butter, black bread and my salt and pepper.

Reaching Cologne, we were warned not to fire at churches. We avoided the town and continued north alongside the Rhine.

Duty…and a daughter

News from home took my mind away from war. In February, 1944, we got the first mail since leaving the U.S. A letter from Katy Short, my brother Bill’s wife, congratulated me on the birth of my daughter Susan.

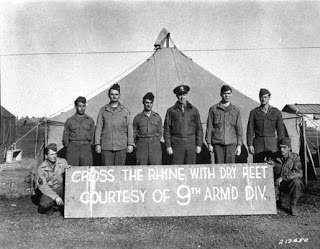

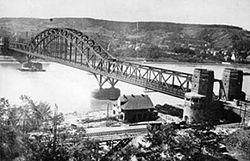

Our division was going down the river looking for a spot to cross when one of our combat command groups came upon a railroad bridge at Remagen and walked across. We were all scared to death to cross, as the bridge was mined and the Germans were in full force on the other bank. One of our infantry half-tracks fell through a shell hole in the bridge. We backed off and fired across the river. Only foot soldiers went across. We waited for orders from Command.

Whiskey proved to be a help. Finding a potato distillery by chance, we persuaded the operator to give us enough to fill our five-gallon water cans with half distilled water and half whiskey. We spent a happy two days dodging bombs from the Luftwaffe who were trying to knock out the bridge, and firing at the Germans across the Rhine.

This bridge, the Ludendorff, was a monster over 300 feet high at the top of the arch. The Germans had the largest gun ever built, “Big Bertha,” on the other side that was mounted on a flatbed train car. One of its shells, about the size of a Jeep, came right over our heads and exploded about 500 yards away.

Our wonderful British Army engineers arrived and built a Bailey Bridge – a bunch of 55 gallon barrels strapped together – about 200 yards from the Ludendorff. Our tanks, slowly and one at a time, took just over 20 minutes to get across.

Meeting Patton’s “pearls”

My tank had locked up and was moving slowly up a very narrow, steep road when I got the chance to meet another George – General Patton. Hearing banging, I looked up through the hatch in the top of my tank and there he was, straddling the opening, looking down at me. It was a tense discussion. He wanted to get past me and was ordering me to scuttle my tank by running it over the side of the cliff. He said my tank was too slow. When I wasn’t cooperating, he pulled out one of his pearl-handled revolvers and threatened to blow my head off if I didn’t obey. Fortunately, one of his aides calmed him down. He also saw my machine gun pointing at his crotch. And why was the General in such a hurry? He had a Life Magazine crew waiting to take his picture capturing the first autobahn.

Once on the autobahn, everything moved faster. Our orders were to head for Limburg, a town just east of Koblenz and on the Lahn River, a tributary of the Rhine. A prison camp for Allied officers had to be liberated as soon as possible. Our speedometers went only up to 25 mph but we were certainly going faster than that.

When we reached the Lahn River, my tank was acting up so I stopped to fix it. This saved my life as four tanks had gotten across the bridge before the Germans blew it. We listened in horror on our radios as the Germans ordered our men to surrender, and then dropped hand grenades into each tank, killing everyone inside.

Reaching the camp, we were ordered to check out a group of buildings inside a fence. I drove my tank through the locked gate and saw a pile of naked bodies in the snow. Inside we found wounded soldiers lying on litters. They had had no medical treatment and some had starved to death when they got too weak to shuffle to the center of the room for a bowl of soup. They had all soiled their pants. Life Magazine’s plane landed on the autobahn and a few years later I saw the photographs they took. One showed one of the wounded GIs, just skin and bones.

Ironically, there was a new German hospital across the road from the camp. I went in and found a few German soldiers in a ward. We forcibly marched the hospital staff and the soldiers across to the other camp and made them clean up and move our wounded and dead soldiers. I believe this was a sub camp of Flossenburg Concentration Camp, built in 1944 by the SS.

Up the river from the camp was the town and that night, our British friends built us another Bailey bridge and just before daybreak we crossed and surprised the Germans, including the townspeople. They resisted but we were in no mood to delay any longer. The prisoners we took were put in a cattle pen by the river. When we reached yet another prison camp we discovered that all the Allied officer prisoners had been moved out during the night. I was detailed to clean out the officers’ quarters and found the commanding general waiting to surrender. He imperiously told me to get our commanding officer because he would surrender only to him. After seeing the atrocities and hearing stories of our men being slaughtered, I was in no mood to honor his demand. I borrowed an infantryman’s rifle with a bayonet and got the general to join the other prisoners after a few jabs in the rear. I wanted to shoot him but couldn’t do it in cold blood. I did, however, take his Luger pistol, which I still have.

The conditions of our men in the camp outraged many of us enough to break rules and take it out on the Germans. Military Police arrived and ordered us to move to a nearby town to cool down.

The town held a pleasant surprise. While checking out a row of houses I came upon a home for nuns. My knock brought a sister to the door who refused, in perfect English, to let us in. I explained we only wanted to be sure there were no German soldiers inside. I found out she was born in Chicago and had been in Germany for many years. When I asked her to get a Bible and swear there were no soldiers hiding, she told me they had two wounded men in the basement. I assured her our medics would treat them.

She and I had a long talk later. She had been away from Chicago for almost ten years. We brought her one of our men from Chicago and she broke down and cried.

Many years later an artist/sculptor friend in Laguna Beach, Ollie Fisher, invited us to dinner to see her new work done in Germany. The first one we saw was of this same little town with a river in front and a church at the back. Ollie gave me this picture and it sits in our living room to this day.

While involved in the capture of the town of Euskirchen, just west of Bonn, I took a bullet that was stopped by my shoulder blade. Medics patched me up and we kept moving.

From there we took an eastward path towards Leipzig, where the plan was to meet up with the Russians. Our destination Kassel, 130 miles away, was a disaster zone. Allied bombing had reduced it to rubble and dust. Residents had fled. As we were emerging from a forest I spotted an anti-tank gun pointed at us. I told our gunner to traverse left to eleven o’clock and fire, but just as he was turning, they put a shell through my gas tanks and blew us up.

Our big gun had been knocked over my hatch blocking my exit so I had to go out the other driver’s hatch. Our assistant driver had arrived from Garland, Texas only a week before. He was standing with the hatch open, frozen in fear. I grabbed his crotch to wake him up and out we went as the fire was scorching me. I hollered to a lieutenant in another tank to throw me a gun, as I had no weapon. Just as he threw it, a shell hit his tank and splattered all of us with shrapnel. When I got up I realized they were firing shells that exploded about twenty feet in the air. I told my buddy, “Let’s run to the cellar just across that small plowed field.” We had four or five grenades to throw in the cellar first.

About half-way there, a shell exploded above us and killed my buddy instantly and almost finished me. The next thing I remember was trying to raise my head from dirt, as I was lying face down in this field. I heard someone say, “That one is alive, he just moved.” Two graves registration men were picking up the bodies.

The final chapter in George Short’s memoirs tells how his soldier brother became his saviour . . . and coming home to his post-war Texas life.

George and Mary Katherine “Mary Kate” Novotny Short had two children: Fred Olsson Short, born 24 January 1942 and Susan Katherine Short, born 26 January 1944.

Fred was killed when hit by a car while changing a tire on a Los Angeles freeway in 1970. Susan married David L Fallen in 1968 and they had two sons, John and James. Mary Kate, by then divorced from George, died in 1980. George later married Joan Pampinella. He died in Newport Beach, California, on 14 July 2003. His brother Bill died in 1996, their sister Betty in 2001. Their brother Bob died in October, 2012.

(This narrative was compiled by Dianne West Short, who is married to brother Bill’s son. The facts were pared with the assistance of writer Patrick Cornish in Perth, Australia.)

© Dianne West Short – 2012-2016 All rights reserved.

3 thoughts on “From Hitting Homers to Hitting the Hun”